Brooklyn’s only meadery sits a few hundred feet from the east branch of Newtown Creek, a Superfund site—thanks to its high concentration of polluted metals, polychlorinated biphenyls and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons—that snakes off the East River and into the borough, dead-ending abruptly at the DC Cabinets Factory on Metropolitan Avenue.

The meadery, Enlightenment Wines, is three blocks south, across the tracks of the New York and Atlantic Railway, past graffitied walls, amid the rumble of box trucks and forklifts busily crisscrossing the neighborhood, facing two vacant industrial Quonset huts, on Scott Avenue. This is somewhere in the cleavage of Williamsburg and Bushwick, perilously close to Queens.

A meadery produces mead, which is honey wine. Humans have been drinking the stuff since at least 7,000 years before Christ performed his oenological miracle in Galilee. The ancient quaff exists thanks to fermentation: a chain of chemical reactions involving glucose, fructose, pyruvate decarboxylase, carbon dioxide and—at last—ethanol. That’s the good stuff. It’s a far more pleasant bit of chemistry than what roils in the creek a stone’s throw north.

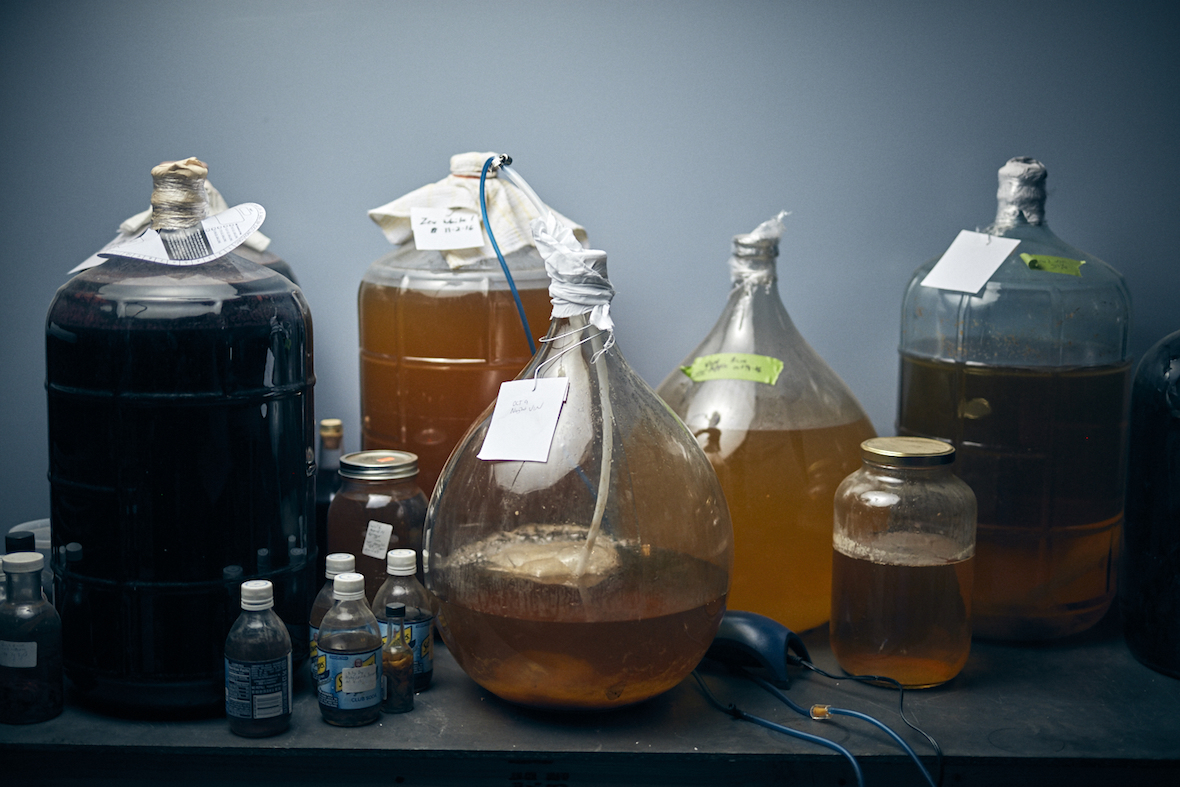

Raphael Lyon—skinny beneath a large, loud sweater, thinning yet wild hair, stubble, tired yet kind eyes—is Enlightenment’s mead chemist. He’s the son of artists and herbalists, and on a recent evening he stood in his large cement-floored workspace, surrounded by a dozen large wooden barrels, glass bottles of all shapes and sizes and a microscope, beneath a long shelf of books about potables. One lay open to an ancient Egyptian diagram, while a disco ball in the corner cast a glimmer over the room. He sniffed a sprig of lemon-mint marigold.

“It’s very common for people to think about designing clothes or chairs,” Lyon told me. “They don’t necessarily think about designing liquids.”

Enlightenment Wines, which opened over the summer, claims to be New York City’s first meadery (San Francisco, both Portlands and a few other cities already have at least one), and I could not—despite sincerely exhaustive efforts—find any evidence to contravene the claim. In Brooklyn, home to many fine breweries, distilleries, a ginsmith and a vermouthier, this inception comes as a genuine surprise.

Adjoining the meadery is Honey’s, its tasting room and cocktail bar. Like the meadery, it’s half Bushwick-industrial, half whimsical-herbalist. An enormous pane of wire-mesh security glass provides the backsplash, while on the galvanized metal bar sat a number of rare geraniums that smelled like peppermint. In frosted glass bottles, with artful labels designed and silk-screened in-house, waited the seasonal mead selection, glowing out in shades of dandelion, jam and hickory and sporting names like Saturnalia, Dagger and Night Eyes.

If the bar is the R&D department, then Arley Marks, Lyon’s partner in mead, is the research director. Marks—no sweater, yes beanie—has herbalist-artist parents, just like Lyon. Also like Lyon, he grew up in New York State—“off the land, chickens and goats, totally self-sufficient.”

“That’s what we’re building here, even though it’s an urban environment,” Marks said. “We’re building our resources from the bottom up. It’s completely vertically integrated production, straight up to the glass or into the cocktail. It’s that similar sort of ethos.” Enlightenment’s honey comes from western New York State. Its beekeeper “avoids moving [the bees] around for pollination, which is how most beekeepers actually make money. His bees are more relaxed and more healthy, so they make better honey.” And while chilled out bees and artisanal mead cocktails are less upstate-subsistence-farming than hipster-Brooklyn-specialty, the obsession and work ethic and detail are nevertheless obvious.

I perused a stained and crumpled menu from the bar. (“We had a rager here last night,” Lyon said, explaining its sad state.) Night Eyes ($35 a bottle) is “co-fermented apple-cranberry-cherry mead with rosehips and hibiscus.” Dagger ($25) is “tart cherry, yarrow, chamomile and foraged hemlock.” And there are the cocktails. There’s the Lucid Dreamer ($12): rum, amaro sfumato, salt, mugwort and egg white. And the Esperanza Flip ($12): tequila, Cardamaro, lime, aquafaba and anisette. It helped to have a dictionary on hand.

Mead—its modern experimentation in Bushwick notwithstanding—wears a millstone of medieval history around its bottle’s neck. While evidence of its production has been found by archaeologists in Neolithic Chinese villages dating to around 7,000 BC, it’s often associated with Vikings, castles, hobbits or monks. The Exeter Book is a 10th-century codex and one of the oldest volumes written in any kind of English—a foundation of the language’s literature. The volume contains a number of riddles, the 27th of which partially reads, in Old English:

Ic eom weorð werum, wide funden, brungen of bearwum ond of burghleoþum, of denum ond of dunum. Dæges mec wægun feþre on lifte, feredon mid liste under hrofes hleo.

“I am valuable to men,” goes the modern translation. “Found widely, brought from woods, and from mountain slopes, from valleys and hills. By day wings bore me in the air, bore me with skill, under the protection of the roof.”

The riddle’s answer, of course, is “mead.” (The wings belong to the bees.)

Beowulf, the millennium-old, 3,200-line epic poem about the monster Grendel laying siege to a Danish mead hall, contains 17 explicit references to mead, mead houses and mead benches. The drink also appears in some form in Chaucer (“He sente hire pyment, meeth, and spiced ale”) and Milton (“Their drink is better, being sundry sorts of meath”) and Shakespeare (“Metheglin, wort, and malmsey”) and Hardy (“I found the mead so extremely alcoholic”).

But Enlightenment Wines is oddly defensive about its libation’s medieval connotation. It tries repeatedly to forestall it, for example, in its website’s FAQ:

Q: I thought mead was from Vikings and Renaissance fairs?

A: No, not really! While there is historical evidence that English and Scandinavian cultures made mead, there is nothing special about this fact. Mead has been made by almost every human culture, as far back as we can find them. It does not belong to Europe alone. The oldest meads are found in China and India, and the strongest mead cultures today are found throughout Asia and Africa. Much of it is made by women. The singular association of mead with white male Europeans, particularly those with beards and axes, is an unfortunate and inaccurate stereotype—one that has been repeated both in the popular press and, even worse, by the mead industry itself. Enlightenment Wines hopes to educate the public with an accurate history of honey-based wines, one that has always been coupled with innovation, local agriculture, and sense of place.

Q: But mead is definitely Olde English [sic] and made by monks, right?

A: Zzz See above.

I arrived at E. W. / Honey’s one recent Saturday afternoon, some 1,000 years after the end of the Viking age, for its holiday fair. The hot pink and blue poster advertising the event featured a trippy Hermetic woodcut and advertised “handmade ceramic sex toys” and “artisanal artists’ art” and would likely be met with great consternation by the likes of Chaucer or Erik the Red. The atmosphere was, as Marks was apt to say, “chill.” I met a friendly man who specializes in wormwood liquors, and there was (I’m not joking) a beekeeper standing at the bar. Hip, 21st-century Brooklyn children darted around, their hip parents not far behind.

But the medieval connotation is hard to shake. A regular couple at the bar drinks mead and plays Dungeons & Dragons at a table in the corner, and Lyon is apt to use terms like “herbarium.” But there are two ways Enlightenment is trying to break the spell of history with which it has grown weary.

One is experimentation. Mead is mutable. It can be reinvented and even redefined. “For me, it’s a really open space to be creative inside of,” Lyon said. The second is education. Many entering Honey’s (myself included) are mead neophytes or burdened by a preconception of a treacly beverage in dusty bottles. “Education is the main thing,” he added. “There’s a lot of education we have to do on behalf of the industry. We have to educate people that mead can be a dry wine, that it can be a really high-quality, premier, prestige beverage.”

For Lyon, his wines’ structure, which is only subtly affected by the kind of honey (say lavender or clover) used, is important above all. When you quaff them, they should have a beginning, a middle and an end.

For Lyon, his wines’ structure, which is only subtly affected by the kind of honey (say lavender or clover) used, is important above all. When you quaff them, they should have a beginning, a middle and an end. They should tell a story. The beginning is the smell, which gives way to the middle—the taste, body and texture—which gives way to a clean, tight finish. Ideally, the story comes full-circle.

And don’t they tell a story? Hasn’t mead, and the bards who’ve drank it, told a story for centuries that continues today? Doesn’t Lyon’s and Marks’s tinkering in their industrial Bushwick lab evoke, if you squint, the experimentation of those ancient Chinese villagers, learning and exploring the joys of the miracle of fermentation?

At the bar, by candlelight, Lyon and Marks discussed the intricacies of the flavors of wormwood and cardamom, the dysfunction of their water heater and the arrival of a new neon sign. I was poured a Dagger Martinez ($12). It contained Breuckelen Distilling‘s oak-aged gin. The simple syrup, I was told, had been augmented with gum arabic so that the flavors better clung to my tongue. The glass’s rim had been encrusted with a powder of sugar and Christmas tree needles. The Dagger mead gave it a rich, winter red. The attention to detail was both laughable and moving. It was delicious.

It was a Tuesday evening, and the bar was open for business. But there wasn’t a customer in sight. I sat and sipped and was happy. I asked how business had been. Good, they assured me.

“There was a woman who came in,” Lyon said. “She looked totally normal. She literally drove in from Long Island or New Jersey. She was, like, a huge mead fan.”