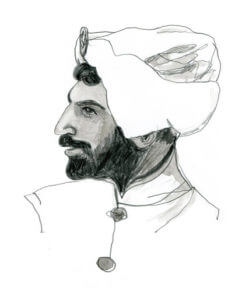

His complex curry dishes transfixed diners. Women swooned over his good looks and swagger (we’re told). Once, a reporter from The New York Letter characterized him as having “clear dark skin, brilliant black eyes, smooth black hair and the whitest of teeth.”

This man was J. Ranji Smile, one of America’s first celebrity chefs and the self-proclaimed “King of Curry Cooks.” In 1899, he was poached from Cecil in London by New York restaurateur Louis Sherry to work at his namesake restaurant on 44th Street and Fifth Avenue, across the street from Delmonico’s.

The city was captivated by Smile’s arrival. Like most immigrant cuisine, Ranji’s food was exotized by those who were new to it. “You take a seat at one of the dainty tables,” the journalist wrote, “look over the India menu with a sort of fear and trembling of what’s to come, with a delightful uncertainty pervading your soul.”

By 1907, Smile was touring the country, performing cooking demonstrations at department stores and food halls. He even offered classes to housewives and was interviewed by Harper’s Bazaar. His culinary prowess and stunts would be chronicled in national press for 15 years. No one seemed to mind that he was also an undocumented immigrant by way of Karachi. That is, until he applied for U.S. citizenship.

Last month, in a public talk at Brooklyn Historical Society, historians Sarah Lohman and Vivek Bald explored the story of curry in American cuisine, the rise and fall of Smile’s celebrity and how xenophobia affected his life in America.

Lohman, author of Eight Flavors: The Untold Story of American Cuisine, examines the diverse history of American tastebuds via eight ingredients, highlighting how Smile pioneered Indian dishes in New York City restaurants. Bald focuses on histories of migration and diaspora, particularly from the South Asian subcontinent, in Bengali Harlem and the Lost Histories of South Asian America. He’s currently working on what will be the first in-depth biography written about Smile.

Upon researching, Bald realized that Smile “found himself in the fantasy that some Americans had about India” because, at the time, there was a crazed obsession over “Orientalism.”

“[Smile] was clearly very good at playing that role of performing and delivering the fantasy that his audience and diners wanted,” Bald explained.

Many Americans loved co-opting Indian culture by spending money on spices and goods or dining at places where Smile mesmerized them with his opulent tableside service and curry dishes.

Smile’s emergence in America happened during what we now lionize as a prime moment for immigration, Bald explained. But in fact, the era was defined by exclusion laws that predominantly barred Asians—despite the intense fascination with India, “the East” and “Oriental” culture.

In 1904, Smile went before a Supreme Court judge (before citizenship tests existed) to petition for citizenship. Lohman explained that it’s not certain whether he applied out of a “true feeling of patriotism or a fear of deportation.” Even though Smile was once lauded in the Associated Press for “his seductive manner that pleases the public so much,” he was denied. At the time, immigration law was still dominated by the first immigration act of 1790, where only a “free white person” was eligible for citizenship. He managed to stay in the country.

But when the Immigration Act of 1917 was signed into law, South Asians were officially barred from immigrating to the United States. Ranji’s chances of becoming a citizen diminished completely.

Lohman explained that two months later, Smile, along with every other man of age in the country, had to fill out a draft card to fight in World War I. Even though South Asians were banned from becoming citizens, they were expected to put their lives on the line for their adopted country. He didn’t fight in the war and eventually left the U.S.—a country he called home for 30 years—for England after his fiftieth birthday.

“He wasn’t even a second-class citizen because he couldn’t even be a citizen,” Lohman said.

In this country, the food of other nations has always been more culturally palatable than their people. While diners dig into their deep pockets to feast at high-end Indian restaurants like Paowalla, Pondicheri and Rahi, one has to wonder: Do any know the legacy and downfall of Smile?