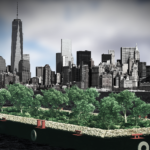

If you haven’t yet paid a visit to Swale—the impressive edible forest garden growing on a barge in Brooklyn Bridge Park—now would be the time. Closing for the winter November 15, the floating food forest since July has made its way from the Bronx to Governors Island and now to Brooklyn.

The brainchild of Brooklyn artist Mary Mattingly, Swale was inspired by an obscure New York City law that prohibits the growing of food on public land, which Mattingly maneuvered her way around by growing food on the water. Since July, she and collaborators have opened the space to the public for tours, workshops, talks, dinners and volunteer ops, engaging the public in hands-on and often delicious ways to explore and rethink our local food culture.

We got the chance to catch up with Mattingly as she wraps up this project for 2016 with hopes to continue the venture in the coming spring:

Edible Brooklyn: Can you give an overview of the project? What it is, what inspired it and how it came to be?

Mary Mattingly: Swale is a public floating food forest in New York City. It is designed as an experiential artwork, site (and instigator) for long-term accessible, free public food. Swale’s mission is to highlight the importance of fresh, healthy food, and access to clean water as a right for everyone. It continues a movement for regenerative food and water-based ecosystems in urban spaces, and is also an active event space. We want to reinforce water as a commons, and work toward fresh food as a commons, too.

EB: What’s a food forest?

MM: Food forests are human-made ecosystems generated through companion-planting methods that involve a dense garden of edible plants tested to support and nourish each other, naturally fighting pests and attracting pollinators. Edible forests can allow us to eat more interdependently from within our surroundings, and over time, inexpensively provide fresh food in places it is lacking. Because of their natural regeneration, they are one of the most resilient agro-ecosystems as well as a sustainable means of food production.

EB: How in the world did you execute this project?

MM: A lot of people have lent a hand in building Swale. It would not have happened without a team who really believes in the project, the NYC Parks Department, A Blade of Grass and without King Marine in Verplanck, New York. We also had a lot of support from the U.S. Coast Guard and nurseries in the tri-state area, including Kean University and the New York City Permaculture Network.

EB: This is public art (is that how you’d describe it?), what were/are you hoping to express to the public? Can you give a word about how you see the role of public art?

MM: Swale is both representative and active. It’s experiential from the moment you walk onto a forest that’s moving. It’s also symbolic in the sense that it’s a proposal. It is a symbol for a potential New York City and it asks what if fresh, healthy food could be a commons, a public service that is part of the urban plan? Art can be an imaginative space and function as an autonomous zone. In this case I believe it can provide more space to interrogate predatory economics and the violence inherent in types of consumption while co-creating an alternative—that will hopefully become more mainstream. I hope it allows us to rethink ideals around commodities, value and the commons, together.

EB: Why food, why now? Do you feel like the issue of food is rising in importance?

MM: Because of frustration over our corporate, industrialized, toxic food system, and love for people as well as everything else affected by it. Working toward a more holistic food system is important for many reasons, including the many injustices generated from industrial food systems.

As city dwellers, we are largely sustained through continual inputs of food, water, energy and material goods, as well as outputs of different forms of “waste.” The supporting agricultural system alone relies on chemicals, fossil fuels, water, land grabbing and long-distance transportation that negatively affect people, the environment and contribute toward climate change. Because the large scope of extraction-based supply and waste chains are mainly invisible to the user, the material flows of resources are difficult to comprehend. This makes land, resource and labor protection difficult. The flow of goods to and from cities has become the root of an ecological and social crisis across the world.

Locally, most food inputs arrive in New York City by way of Hunts Point in the Bronx, with over 10,000 trucks delivering food each day. Many of New York City’s 8.4 million inhabitants suffer from the pollutants and chemical contaminants brought on by supply and waste chains, yet even with access to plenty of food sources, one in six New Yorkers live in households facing food insecurity. Large areas in each borough are considered “food deserts” due to lack of fresh food within a reasonable distance. Because of these inequities, there is a vibrant, diverse and exponentially growing food justice and policy movement throughout the city. More than ever, we realize the need for multiple forms of resiliency.

EB: I’ve read your manifesto, which resonated. Can you briefly describe for our readers how you work as an artist, what motivates you; maybe a big picture overview of your way of thinking?

MM: I’ve been formulating a way of making art that’s based in nonviolent action. That to me means all aspects of our art life—from creating independent supply networks to making principled art. It came out of a series of circumstances in my life that culminated in me needing to write this—and knowing that art has a lot of power, and artists can use that to co-create worlds we believe in and network them together.

EB: This project started in the Bronx (in July?), traveled south to Governor’s Island and now resides at Brooklyn Bridge Park. Can you describe what the response has been from the public? Do you have a sense of how many visitors you’ve had.

MM: Throughout the summer and fall, Swale averages 500 visitors a day, three workshops or events a week, and four group tours a week. People have brought plants to Swale constantly, which has been unexpected. We care for them on Swale and share them with everyone who comes onboard after.

EB: Can you describe how the public has engaged, as visitors, volunteers or otherwise?

MM: People come onboard Swale to pick food, or to just see what is going on. Some people come for space—they have lunch at a table, or relax with family/friends. It’s a space that has a different pace than most of the city. Now, people come onto Swale and ask if they can help, that’s how it’s continued to unfold.

EB: I know you have a long list of collaborators, can you briefly describe how these collaborations have unfolded? Have they continued to unfold?

MM: Yes, at first I contacted people I knew who had particular skills or interest around food / public art / water. Our group is largely made up of about 25 people I have met with similar passions working toward similar, urgent goals of regeneration, local sustainability. Often these are people who work toward equal distribution of wellness across this city and beyond. Since forming a team of people through friends in the beginning of the project, we receive e-mails and visitors who are interested in working on Swale. This is how the project has continued to evolve. Everyone brings different skills and interests to the project and therefore it can take on a diverse set of directions.

EB: You’ve held classes, dinners, lectures, tours at Swale since its beginning, can you give a brief overview of the scope of Swale’s activities.

MM: It’s a very open space. People suggest ideas and we see if they can co-facilitate with us. We do projections, performances and screenings with Biome Arts, a collective collaborating with Swale. We also host meals, poetry readings, presentations, seed swaps and workshops.

EB: In terms of how you originally saw this project, is it now as you anticipated or has the project evolved?

MM: It has evolved. At first I thought we would make the barge, but we weighed that timeline with the urgency we all feel around the subject.

EB: I understand part of the impetus for this project was an antiquated city law that prohibits growing food in public places. Can you describe this law and your thoughts on it.

MM: In New York City picking plants in public spaces is considered destruction of property. This law was created in order to protect public lands from being over-foraged. It has also been enforced due to more recent turns in New York City’s park maintenance. As a public food forest, Swale can only exist in New York because it is on the waterways. The waterways are the closest space we have in New York to a true commons.

EB: Have you gotten feedback from any city organizations that maybe have some say over this law?

MM: Yes, the best news is that perhaps the city can create a test space for public foraging, or perhaps Swale can stay at a public dock.

EB: Do you have anything you’d like to say about your fiscal sponsor, the New York Foundation for the Arts?

MM: We have been able to work with NYFA and also A Blade of Grass closely. NYFA has provided us with their nonprofit status so we have long-term fundraising options open to us, which is very important for the stability of Swale. A Blade of Grass provided us with the seed money to begin the project.

EB: Any surprises, good or bad, or both?

MM: The amount of plants people have brought onto Swale, and the support we have found from people who have just stumbled upon the project have kept us all dedicated to making Swale long term.

EB: How about the future of Swale. Do you have plans for overwintering? Spring and Summer 2017?

MM: Yes, we have plans to overwinter at King Marine in Verplanck and then continue the project in the spring and summer. With our partner organizations including Youth Ministries for Peace and Justice, the Bronx River Alliance, Partnership for Parks, Rocking the Boat and the Point, we would like Swale to find a permanent home in the Bronx. To do this, we are working toward a long-term maintenance plan with the NYC Department of Parks. Simultaneously we are working on public land in New York City where the edible perennial plants on Swale can be transplanted and accessible to anyone.

Photos courtesy of Swale.